HMS Centaur (1797)

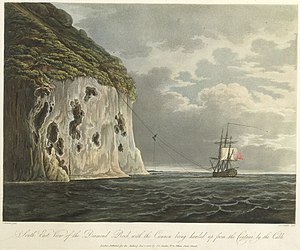

HMS Centaur at Mount Diamond, Martinique | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | HMS Centaur |

| Ordered: | 17 January 1788 |

| Builder: | Woolwich Dockyard |

| Laid down: | November 1790 |

| Launched: | 14 March 1797 |

| Honours and awards: | Naval General Service Medal with clasp "Centaur 26 Augt. 1808"[1] |

| Fate: | Broken up, 1819 |

| General characteristics [2] | |

| Class and type: | Mars-class ship of the line 74-gun |

| Tons burthen: | 184224⁄94 (bm) |

| Length: |

|

| Beam: | 49 ft (15 m) |

| Depth of hold: | 20 ft (6.1 m) |

| Propulsion: | Sails |

| Sail plan: | Full rigged ship |

| Armament: |

|

HMS Centaur was a 74-gun third rate of the Royal Navy, launched on 14 March 1797 at Woolwich. She served as Sir Samuel Hood's flagship in the Leeward Islands and the Channel. During her 22-year career Centaur saw action in the Mediterranean, the Channel, the West Indies, and the Baltic, fighting the French, the Dutch, the Danes and the Russians. She was broken up in 1819.

Contents

1 Service in the Mediterranean

2 Service in the West Indies

3 The Channel and Eastern Atlantic

4 The Baltic

4.1 Anglo-Russian War

5 Return to the Mediterranean

6 Channel Fleet

7 Final years

8 Notes, citations, and references

Service in the Mediterranean

Captain John Markham commissioned Centaur in June 1797 and the next year sailed for the Mediterranean. In November she participated in the occupation of Menorca (historically called "Minorca" by the British).

On 13 November, Centaur, HMS Leviathan, and HMS Argo, together with some armed transports, relatively unsuccessfully chased a Spanish squadron. Argo did re-capture the British 16-gun Pylades-class sloop HMS Peterel, which the Spanish had taken the day before.[3]

The next year, on 2 February 1798, Centaur pursued two Spanish xebecs and a settee, all privateers in royal Spanish service. She captured the privateer La Vierga del Rosario, which carried fourteen brass 12-pounder guns and had a crew of 90 men. The other two vessels escaped.[4]

A year later, on 16 February 1799 Centaur, Argo and Leviathan attacked the town of Cambrils. Once the defenders had abandoned their battery, the boats went in. The British dismounted the guns, burnt five settees and brought out another five settees or tartans laden with wine and wheat. One tartan, the Velon Maria, was a letter of marque, armed with one brass and two iron 12-pounders and two 3-pounders. She had a crew of 14 men.[4]

Then on 16 March 1799, she and Cormorant drove the Spanish frigate Guadaloupe aground near Cape Oropesa. Guadaloupe, of 40 guns, was wrecked.[5]

In June, Centaur was involved in a brief action off Toulon before elements of Admiral Keith's fleet joined her. Centaur and Montagu fired at a brig-corvette and several settees off Toulon. They were then able to capture and destroy four of the settees.[6]

In the Action of 18 June 1799, Markham's squadron captured a French squadron consisting of the 40-gun Junon, 36-gun Alceste, 32-gun Courageuse, 18-gun Salamine and 14-gun brig Alerte.[7] The British took the captured vessels into service under their existing names, except that Junon became Princess Charlotte and Alerte became Minorca. Soon after, Centaur returned to England.

While working in the Channel in late 1800 and early 1801, on 25 January 1801 Centaur sent the Danish galiots Bernstorff and Rodercken into Plymouth. The Danish ships were carrying bale goods and nuts.[8]

Under Captain Littlehales, while serving with the Channel Fleet, Centaur and her sister ship, Mars, collided off the Black Rocks during the night of 10 March. Centaur lost her main and main-top-mast, which killed two men and injured four as they fell.[9]Mars lost her head, bowsprit, foremast and main top-topmast and then almost grounded near the Île de Bas. In the last moment Canada was able to get a tow rope on her. Canada then towed Mars into Cawsand Bay.[10] The subsequent court martial acquitted Mars's captain and lieutenant of any negligence, but sentenced a lieutenant from Centaur to the loss of six months' seniority and dismissal from his ship.[11]

Service in the West Indies

Late in 1802, Centaur sailed to the West Indies where she joined Vice Admiral Sir John Thomas Duckworth's squadron in Jamaica. When Commodore Sir Samuel Hood arrived to take command in the Leeward Islands, he raised his pennant in Centaur.

On 26 June 1803 Centaur participated in the capture of Saint Lucia and its citadel, Morne Fortunée; three days later the expedition took Tobago from the French.[12] The fleet went on to capture the Dutch islands.

On 21 August 1803, Centaur and Netley captured the American ship Fame and her cargo of flour and corn. Then on 31 August Centaur detained the Dutch ship Good Hope, which was carrying wine and cordage.[13]

On 20 September the British seized Demerara.[14] The corvette Hippomenes, which was acting as a guard ship at Fort Stabroek, where she looked after the Governor's maritime affairs and served as harbour master for visiting ships,[15] was the only vessel belonging to the Batavian Republic there and was included in the terms of capitulation.[16] The British took her into service as HMS Hippomenes.

In September Hood also received the assignment to blockade the bays of Fort Royal and Saint Pierre, Martinique. On 22 October Centaur captured the French privateer Vigilante. She was armed with two guns and had a crew of 37 men.[13] The pursuit took seven hours.[17]

Centaur was sailing past Cap des Salinés, Martinique, early in the morning of 26 November when a battery fired at her. Hood had Maxwell anchor in Petite Anse d'Arlette. Then a landing party made up of Centaur's marines and about 40 sailors destroyed the battery. They also threw its six 24-pounders over the cliff. The militia guarding the battery had a brass 2-pounder gun but fled without putting up any resistance even though the landing party had to climb a steep, narrow path. Unfortunately, the premature explosion of the battery's magazine cost Centaur one man killed, and three officers and six men wounded, the only casualties from the operation. Then Centaur discovered another battery, this one armed with two 42-pounders and a 32-pounder, between the Grande and Petite Anse d'Arlette. The French abandoned the battery when a landing party approached. Once again, Centaur's men threw the guns over the cliff and destroyed a barracks and the ammunition stored there.[18]

Centaur was anchored in Fort Royal Bay, Martinique, when on the morning of 1 December she sighted a schooner towing a sloop. The pair were about six miles away and Hood believed that they were on their way to St. Pierre. He therefore instructed Maxwell to take Centaur in pursuit.[13] Their prey did not initially notice them, but when they did, the schooner let go her tow and the vessels separated. After a pursuit that extended over 24 leagues, Centaur captured the schooner. She turned out to be the privateer Ma Sophie, out of Guadeloupe.[13] She had a crew of 46 men and had had eight guns that she had thrown overboard during the chase in an attempt to increase her speed.[13] When Ma Sophie and the sloop separated, Centaur sent the Sarah, an advice boat, after the sloop, which she captured.[Note 1].

Hood decided to use Sophie as a tender to Centaur. Lieutenant William Donnett became her captain with the task of monitoring the channel between Martinique and Diamond Rock, a basalt island south of Fort-de-France, the main port of Martinique, for enemy vessels. Subsequently, Donnett and Sophie frequently visited the Rock to gather both the thick, broad-leaved grass that the crew could weave into sailors' hats, and a spinach-like plant called callaloo. Callaloo, when boiled and served daily, kept the crews of Centaur and Sophie from scurvy and was a nice addition to a menu too long dominated by salt beef.[20]

In late 1803 and early 1804, Centaur, under Captain Murray Maxwell, established several batteries on Diamond Rock. To ease its administration vis-à-vis the Admiralty, The British commissioned the rock as HMS Diamond Rock. Hood garrisoned it with two lieutenants and 120 men under the command of Lieutenant James Wilkes Maurice, his first lieutenant. Unfortunately, at some point during this period and for an unknown reason, Sophie blew up, killing all but one man of her crew.[21] (Diamond Rock fell to an overwhelming French attack on 3 June 1805.)

On 3 February, Centaur sent her boats to cut out the French 18-gun brig-corvette Curieux from the Carénage, under the guns of Fort Edward at Fort-Royal harbour, Martinique.[22] In the fight, the French lost 40 men killed and wounded, and the British had nine men wounded, including all three officers leading the cutting out party. The British took Curieux into the navy as HMS Curieux. Her original commander was Lieutenant Robert Carthew Reynolds, who had led the cutting-out party, but he died of the wounds he had received in the attack. His replacement as her commander was Lieutenant George Bettesworth of Centaur, also a member of the cutting-out party.[23]

On 25 April 1804, Centaur arrived off the Surinam River after a three-week voyage from Barbados. Her flotilla consisted of Pandour, Serapis and Alligator, all three en flute, Hippomenes, Drake, the 10-gun schooner Unique, and transports carrying 2000 troops under Brigadier-General Sir Charles Green. The British proposed surrender terms that the Dutch governor rejected. As an initial step in the campaign, Centaur sent her boats to capture the battery of Friderici. The landing party captured the battery at the cost of four men killed and three wounded. The Dutch surrendered on 5 May and Hood made Captain Conway Shipley of Hippomenes post-captain and appointed him to Centaur. (One day earlier the Admiralty had promoted Shipley into the ex-French 28-gun frigate Sagesse; he later assumed command of her at Jamaica.) Hood next appointed Captain William Richardson of the 28-gun frigate Alligator to command Centaur and the Admiralty confirmed his appointment on 27 September. The British captured two Dutch men-of-war, the 32-gun frigate Proserpine, which they took into service as Amsterdam, and the 18-gun corvette Pylades, which they took into service as Surinam.[24] The British also captured the George, a schooner of 10 guns, and three merchant vessels.[25][Note 2]

On 30 July 1804, Centaur sent her boats into Basseterre Roads, Guadeloupe, where they cut out a schooner of unknown name and of two guns, as well as the privateer Elizabeth, which was pierced for 12 guns but mounting six. She had a crew of 65, most of whom were either killed, drowned, or swam ashore. The boats achieved these captures despite a complete lack of wind and under heavy grape and small arms fire from the batteries and troops that lined the beach. The boats had one man killed and five wounded, and brought out two wounded prisoners. Shipley described Elizabeth as "the fastest sailing Privateer out of Guadaloupe, and has been uncommonly fortunate this War."[27]

Centaur also recaptured another Elizabeth, this one of Liverpool, that Decidé (actually Grande Decidé) had captured while Elizabeth was sailing from the coast of Africa with a cargo of slaves. Centaur detained, on suspicion, the "Grecian" ship St. Nicholas, which was carrying produce from Guadeloupe.[27]Centaur also recaptured the schooner Betsey, which had been sailing in ballast.[28] Then in December, Centaur recaptured the English ship Admiral Peckenham, which was carrying produce.[28]Centaur sailed to England in the spring of 1805, before returning to the Leeward Islands.

Centaur nearly collides with St. George

A year later, on 29 July 1805, Centaur, under Captain Henry Whitby, in company with a squadron under Captain De Courcy, was sailing from Jamaica to join Nelson, when the squadron encountered a hurricane.[29] The storm threw Centaur's masts overboard, carried away her rudder and smashed and sent all her boats overboard.[30] Leaks that had started when Centaur had run ground some weeks before worsened substantially. The crew, especially the marines, labored at her pumps.[29] For sixteen hours they were barely able to offset the water coming in.[30] On the second day of the storm, a huge wave almost brought the first-rate St George crashing into Centaur.[31]

As the hurricane lessened and the seas became a little calmer, the crew was able to get a sail under Centaur, and use her hawsers to lash it to her, much reducing the leaks and bracing her shattered frame.[30] To help keep Centaur afloat, the crew also threw all but a dozen or so guns overboard.[29] The 74-gun third rate HMS Eagle was then able to tow Centaur into Halifax.[29] There Commissioner John Inglefield, who had been captain of the previous Centaur when she foundered after the Atlantic hurricane of 16–17 September 1782, greeted her.[32][Note 3]

At Halifax, Nova Scotia, Centaur was put on her side for repairs. At that time it was discovered that "14 feet of false keel was found off from the fore foot aft, which occasioned the leak."[33]

Officers of HMS Centaur in 1805

Captain Whitby married Catherine Dorothea Inglefield, the commissioner's youngest daughter, around the end of 1805. Whitby wanted to stay in Halifax so he made an exchange into the 50-gun fourth rate HMS Leander.[34] Captain John Talbot of Leander took command of Centaur on 5 December and sailed her home. Because of the damage she had suffered, Centaur missed joining Nelson and therefore being at the Battle of Trafalgar.

The Channel and Eastern Atlantic

In 1806, Centaur was under the command of Captain W. H. Webley and also served as flagship for Captain Sir Samuel Hood, who was acting as Commodore of the squadron off Rochefort. On 16 July, boats from each of the squadron's line-of-battle ships and Indefatigable and Iris engaged in a cutting out expedition on two corvettes and a convoy in the Garonne. Lieutenant Edward Reynolds Sibley, Centaur's First Lieutenant, was badly wounded in the successful attack on the largest corvette, the five-year-old Caesar. Caesar was armed with eighteen guns and had a complement of 86 men, under the command of Monsieur Louis Francois Hector Fourre, lieutenant de vaisseau. One man from Centaur was killed and seven, including Sibley, were wounded. The other French vessels escaped up the river and the British boats that followed them, unsuccessfully, suffered heavy casualties. In addition to the losses from Centaur, the British had five men killed, 29 wounded, and 21 missing, most of whom were apparently taken prisoner.[35]

During the Action of 25 September 1806, Centaur captured Armide, and assisted in the capture of Infatigable, Gloire and Minerve. The British took all of them into the Royal Navy under their existing names. Centaur lost three men killed and three wounded. In addition, a musket ball shattered Hood's arm, which had to be amputated. The wound forced Hood to quit the deck and leave the ship in the charge of Lieutenant William Case.[36]

Towards the end of 1806, Hood received orders to join a secret expedition at the Cape Verde Islands. However, the expedition sailed before Centaur arrived. Hood then took a squadron under his command to cruise between Madeira and the Canaries.[37]

The Baltic

In the summer of 1807, Samuel Hood had received a promotion to rear admiral. On 26 July 1807, Centaur, with Commodore Sir Samuel Hood and Captain William Henry Webley, sailed as a part of a fleet of 38 vessels under Admiral James Gambier and bound for Copenhagen. Between 15 August and 20 October, she took part in the second Battle of Copenhagen when Gambier, together with General Lord William Cathcart, captured the Danish Navy in a preemptive attack. Taking command of the fleet at Copenhagen, he raised his pennant in Centaur on 18 October.[37]

Centaur's deployed her boats to blockade the harbour at Copenhagen and intercept any supplies arriving from the Baltic.[37] At some point, her cutter attempted to take a Danish dispatch boat that was trying to sail from Copenhagen past the island of Moen to Bornholm. The Danish boat ran on shore just past a cliff where the Danes had stationed troops with two field pieces. The Danes on the cliff fired on the cutter, killing the lieutenant in charge and wounding a midshipman. Nevertheless, Midshipman Price, Master's Mate Walcott and the cutter's crew succeeded in taking their quarry and towing her off.[37][Note 4]

By 24 December, Centaur was again briefly in the Atlantic, this time participating in General William Beresford's (friendly) occupation of the island of Madeira.

Anglo-Russian War

In early 1808 Russia initiated the Finnish War in response to Sweden's refusal to bow to Russian pressure to join the anti-British alliance. Russia captured Finland and made it a Grand Duchy under the Russian Empire. The British decided to take counter-measures and in May sent a fleet, including Centaur, under Vice-Admiral Sir James Saumarez to the Baltic.

On 9 July, the Russian fleet, under Admiral Peter Khanykov, came out from Kronstadt. The Swedes massed a fleet under Swedish Admiral Cederstrom, consisting of 11 line-of-battle ships and five frigates at Örö and Jungfrusund to oppose them. On 16 August, Saumarez then sent Centaur and Implacable, under Captain Thomas Byam Martin, also a 74-gun third rate, to join the Swedish fleet. They chased two Russian frigates on 19 July and joined the Swedes the following day.

On 22 August, the Russian fleet, which consisted of nine ships of the line, five large frigates and six smaller ones, moved from Hanko and appeared off the Örö roads the next day. The Swedish ships from Jungfur Sound had joined Rear-Admiral Nauckhoff and by the evening of 24 August the combined Anglo-Swedish force had made its preparations. Early the next day they sailed from Örö to meet the Russians.[39]

The Anglo-Swedish force discovered the Russians off Hanko Peninsula; as the Russians retreated the Allied ships followed them. Centaur and Implacable exhibited superior sailing and slowly outdistanced their Swedish allies. At 5am on 26 August Implacable caught up with a Russian straggler, the 74-gun Vsevolod (also Sewolod), under Captain Rudnew (or Roodneff).[39]

The Russian Ship Vsevolod burning, after the action with the Implacable and Centaur, August 26, 1808

Implacable and Vsevolod exchanged fire for about 20 minutes before Vsevolod ceased firing. Vsevolod hauled down her colours, but Hood recalled Implacable because the Russian fleet was approaching. During the fight Implacable lost six dead and 26 wounded; Vsevolod lost some 48 dead and 80 wounded.

The Russian frigate Poluks then towed Vsevolod towards Rager Vik (Ragerswik or Rogerswick),[40] but when Centaur started to chase them the frigate dropped her tow.[39] The Russians sent out boats to bring her in, in which endeavor they almost succeeded. They did succeed in putting 100 men aboard her as reinforcements and to replace her casualties.

However, just outside the port, Centaur was able to collide with Vsevolod. A party of seamen from Centaur then lashed her mizzen to the Russian bowsprit before Centaur opened fire. Vsevolod dropped her anchor and with both ships stuck in place, both sides attempted to board the other vessel. In the meantime, Implacable had come up and added her fire to the melee. After a battle of about half an hour, the Russian vessel struck again.[39]

Implacable hauled Centaur off. The British removed their prisoners and then set fire to Vsevolod, which blew up some hours later. Centaur lost three killed and 27 wounded. Vsevolod lost another 124 men killed and wounded in the battle with Centaur;[39] 56 Russians escaped by swimming ashore. In 1847 the Admiralty awarded the Naval General Service Medal with the clasps "Implacable 26 Augt. 1808" and "Centaur 26 Augt. 1808" to all surviving claimants from the action.

Vice-Admiral Saumerez with his entire squadron joined the Anglo-Swedish squadron the next day. They then blockaded Khanykov's squadron for some months. After the British and the Swedes abandoned the blockade, the Russian fleet was able to return to Kronstadt.[40]

Return to the Mediterranean

In 1809, Frederick Marryat, who would go on to become a famous author, joined Centaur as a midshipman. He continued to serve under Hood in the Mediterranean.[Note 5]

Capt. John Chambers White brought Hibernia to Port Mahon to be Hood's flagship. White then took command of Centaur.[41]

Centaur participated in the defence of Tarragona when French forces under Marshal Suchet besieged the city from May 1811. Captains Codrington, White, and Adam spent most nights in their gigs carrying out operations under cover of darkness to evacuate women, children and wounded.[42] On 21 June the French broke in. They then reportedly massacred several thousand men, women and children and took many prisoners before setting fire to the city.[43] The boats of the squadron had only been able to rescue some five or six hundred of the inhabitants. On 28 June Centaur's launch engaged the French on a beach at Tarragona, losing two men killed and three wounded.[42]Centaur returned to Plymouth in October 1813.

Channel Fleet

Centaur first sailed to Saint Helen's Island, Quebec, and the Western Isles (the Azores), but arrived off Cherbourg by November 1813. On the evening of 6 April 1814, Centaur arrived at the Gironde. Her objective was to support Egmont in her attack on the French ship of the line Regulus. Also near her were three brigs and some other vessels. All were under the protection of shore batteries there. The plan was that a landing party in boats, to which Centaur had contributed, would storm Fort Talmont while Egmont would take advantage of high tide to attack Regulus.[Note 6] At midnight, before the attack had even begun, it became clear that the French had set fire to their ships, which were totally destroyed by morning.[44][45] Before 9 April, a landing party of seamen and marines from the 38-gun frigate Belle Poule, under Captain George Harris, successively entered and destroyed the batteries of Pointe Coubre, Pointe Nègre, Royan, Soulac, and Mèche.[44]

In January 1819, the London Gazette reported that Parliament had voted a grant to all those who had served under the command of Lord Viscount Keith in 1812, between 1812 and 1814, and in the Gironde. Centaur was listed among the vessels that had served under Keith in the Gironde.[Note 7]

Final years

After the end of the Napoleonic Wars, Centaur made a few more cruises, including another to Quebec, in 1814. In the spring of 1815, under Capt. T. G. Caulfield, she sailed with HMS Chatham from Plymouth to the Western Islands again. On 26 August she left the Cape of Good Hope for England, arriving on 13 November. She was paid off in Plymouth three days later. She was broken up in November 1819.[2]

Notes, citations, and references

Notes

^ The sloop was a prize that Ma Sophie had cut out of Courland Bay, Tobago, and had on board only a few hogsheads of sugar.[13][19]

^ Prize money in the amount of £32,000 was paid in March 1808 to the officers and crew of all the Royal Navy vessels involved in the capture of the colony of Surinam.[26]

^ That same, earlier, hurricane had also sunk Ville de Paris, Ramillies, Glorieux, and Hector, all but Ramillies being prizes from the Battle of the Saintes. The convoy numbered some 94 vessels in all. A number of other British merchant and smaller navy vessels also sank, with the total death toll being around 3,500 men.

^ After this incident, Mr Walcott received a promotion to signal lieutenant. He continued to serve with Hood on several vessels, staying with Hood until Hood's death in Madras on 24 December 1814.[38]

^ While Centaur was cruising off Toulon, Marrayat jumped overboard to rescue a man who had fallen from the main-yard. This was his second such rescue. The first time was in 1806 while he was a midshipman on HMS Imperieuse.

^ Marshall makes clear that the report in the London Gazette,[44] is in error in that the plan for the attack on Regulus herself did not include Centaur.[45]

^ The sum of the two tranches of payment for that service was £272 8s 5d for a first-class share; the amount for a sixth-class share was £3 3s 5d.[46]

Citations

^ "No. 20939". The London Gazette. 26 Jan 1849. p. 242..mw-parser-output cite.citationfont-style:inherit.mw-parser-output .citation qquotes:"""""""'""'".mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registrationcolor:#555.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration spanborder-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon abackground:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center.mw-parser-output code.cs1-codecolor:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-errordisplay:none;font-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-errorfont-size:100%.mw-parser-output .cs1-maintdisplay:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-formatfont-size:95%.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-leftpadding-left:0.2em.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-rightpadding-right:0.2em

^ ab Winfield (2008), p.37.

^ "No. 15091". The London Gazette. 24 December 1798. p. 1233.

^ ab "No. 15119". The London Gazette. 26 March 1799. pp. 288–289.

^ Norie (1842), p. 275.

^ James (1837), Vol. 2, p. 262.

^ "No. 15162". The London Gazette. 23 July 1799. p. 741.

^ Naval Chronicle, Vol. 5, p. 180.

^ Naval Chronicle, Vol. 5, p.371.

^ Naval Chronicle, Vol. 5, pp. 366 & 371.

^ Grocott (1997), pp. 110–111.

^ Southey (1827), Vol. 3, pp.230-1.

^ abcdef "No. 15669". The London Gazette. 24 January 1804. pp. 110–111.

^ "No. 15643". The London Gazette. 12 November 1803. p. 1573.

^ Southey (1827). Vol. 3, pp. 232-4.

^ "No. 15649". The London Gazette. 26 November 1803. pp. 1659–1663.

^ Naval Chronicle, 30 June 1804, Vol. 11, p. 156.

^ Naval Chronicle, 30 June 1804, Vol. 11, p. 155.

^ Southey (1827), Vol. 3, pp.239-40.

^ Boswall (1833), p.210.

^ Boswall (1833), p.212.

^ "No. 15697". The London Gazette. 28 Apr 1804. p. 537.

^ Moore Holdsworth Macpherson, (1926), p.36.

^ "No. 15712". The London Gazette. 19 June 1804. pp. 753–759.

^ "No. 15735". The London Gazette. 8 September 1804. p. 112.

^ "No. 16121". The London Gazette. 20 February 1808. pp. 273–274.

^ ab "No. 15754". The London Gazette. 13 November 1804. p. 1396.

^ ab "No. 15794". The London Gazette. 2 April 1805. p. 436.

^ abcd Ellms (1841), pp.247-261.

^ abc Marshall (1832), Vol. 3, Part 2, pp.229-31.

^ Mechanics' magazine, and journal of the Mechanics' Institute, Vol. 7, p.112.

^ Campbell (1818), pp.346-7.

^ Naval Chronicle, Vol. 17, p.128.

^ Naval Chronicle, Vol. 28, pp.269-270.

^ "No. 15941". The London Gazette. 29 July 1806. pp. 949–951.

^ "No. 15962". The London Gazette. 30 September 1806. pp. 1306–1307.

^ abcd Marshall (1830), Supplement, Part 4, pp.32-33 & 389.

^ Marshall (1830), Supplement, Part 4, pp. 389-90.

^ abcde "No. 16184". The London Gazette. 17 September 1808. pp. 1281–1284.

^ ab Tredrea and Sozaev (2010), pp. 71-72.

^ Marshall (1824), Vol. 2, p.233.

^ ab "No. 16513". The London Gazette. 13 August 1811. pp. 1589–1590.

^ Edinburgh annual register, Vol 4, Issue 1, p.306.

^ abc "No. 16887". The London Gazette. 19 April 1814. p. 834.

^ ab Marshall (1828), Supplement, Part 2, p.291.

^ "No. 17864". The London Gazette. 26 October 1822. p. 1752.

References

.mw-parser-output .refbeginfont-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ullist-style-type:none;margin-left:0.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>ddmargin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100font-size:100%

- Boswall, Captain, RN. (June 1833). "Narrative of the Capture of the Diamond Rock, effected by Sir Samuel Hood, in the Centaur". The United Service Journal and naval and military magazine, Part 2, No. 55, pp. 210–215.

Campbell, John (1818) Naval history of Great Britain: including the history and lives of the British admirals. (London: Baldwyn), Vol. 8.- Colledge, J.J. Ships of the Royal Navy: The Complete Record of All Fighting Ships of the Royal Navy From the Fifteenth Century to the Present. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1987.

ISBN 0-87021-652-X. - Grocott, Terence (1997) Shipwrecks of the Revolutionary & Napoleonic eras. (Mechanicsburg: Stackpole).

- Lavery, Brian (2003) The Ship of the Line - Volume 1: The development of the battlefleet 1650-1850. Conway Maritime Press.

ISBN 0-85177-252-8. - Moore, Alan Hilary & Arthur George Holdsworth Macpherson (1926) Sailing ships of war, 1800-1860: including the transition to steam. (London, Halton & T. Smith).

- Southey, Thomas (1827). Chronological history of the West Indies, (London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, & Green), Vol. 3.

- Tredrea, John and Eduard Sozaev (2010) Russian Warships in the Age of Sail, 1696-1860. Seaforth Publishing

ISBN 978-1-84832-058-1. - Winfield, Rif (2008) British Warships in the Age of Sail, 1793-1817: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. Seaforth Publishing, 2nd edition.

ISBN 978-1-84415-717-4.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to HMS Centaur (1797). |